CISA Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) affecting security controls

Since its inception, I’ve been bullish on the value of the CISA Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog, along with their periodic analysis of the top exploited vulnerabilities based on the same. The KEV catalog contains a concrete set of trailing indicators that tell you which vulnerabilities should be prioritized for patching or other forms of remediation.

For organizations with a mature, operational vulnerability management program, KEV is a valuable input. For the majority of organizations that do not have a vulnerability management program, it’s an excellent place to start. And if we’re being realistic, it’s a good alternative to doing nothing or addressing vulnerabilities ad hoc.

Enriching the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities data set

CISA makes the KEV data set available via CSV or JSON. I’ve been using the CSV version, which I’ve enriched in a number of ways, including identifying different types of products affected by these vulnerabilities:

- Security - Products designed explicitly to secure devices, networks, or otherwise. This includes endpoint and network protection.

- Edge infrastructure - Products used to connect networks, including protecting the network edge by use of access control lists or mechanisms. This includes most routers, firewalls, email gateways, and other devices that accept inbound traffic from the Internet for inspection or routing.

- Identity and Access Management - Products that provide identity, authentication, authorization, and other access management functions.

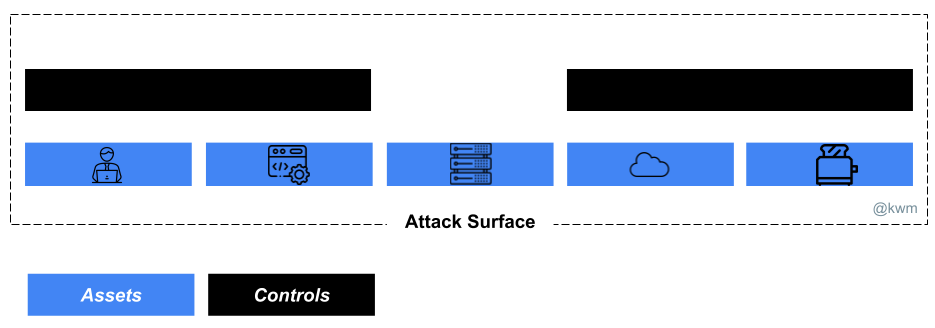

The set of products that fall into any of the above categories are treated collectively as security controls.

I also found it helpful to integrate the top exploited vulnerability lists into the same data set, which makes it possible to see some of the breakdowns below, as well as trends.

Known and top exploited vulnerabilities in security controls

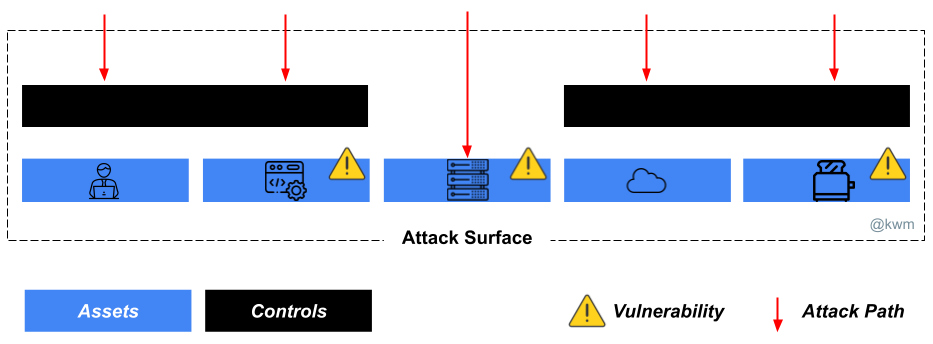

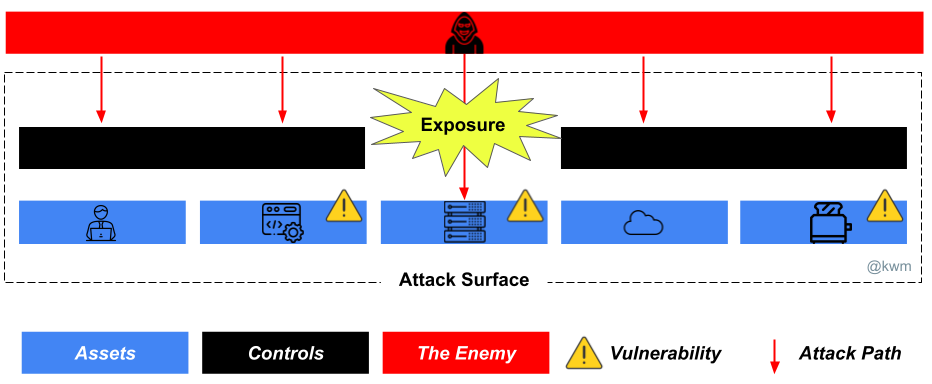

Your security controls are a critical cross-section of your attack surface. While we’re busy using our security controls to monitor devices, identities, and other assets under our protection, adversaries are busy exploiting these controls, gaining tremendous leverage over (often many) victims.

As of October 2023, approximately 17% of KEV entries affect a security control.

More concerning than a known exploit in any security control is the appearance of security controls in CISA’s list of top exploited vulnerabilities. 33% of the top 12 exploited vulnerabilities in 2022 affected security controls. If we look at all 42 of the top exploited vulnerabilities in 2022, ~29% (still roughly 1/3) of the expanded set affected security controls.

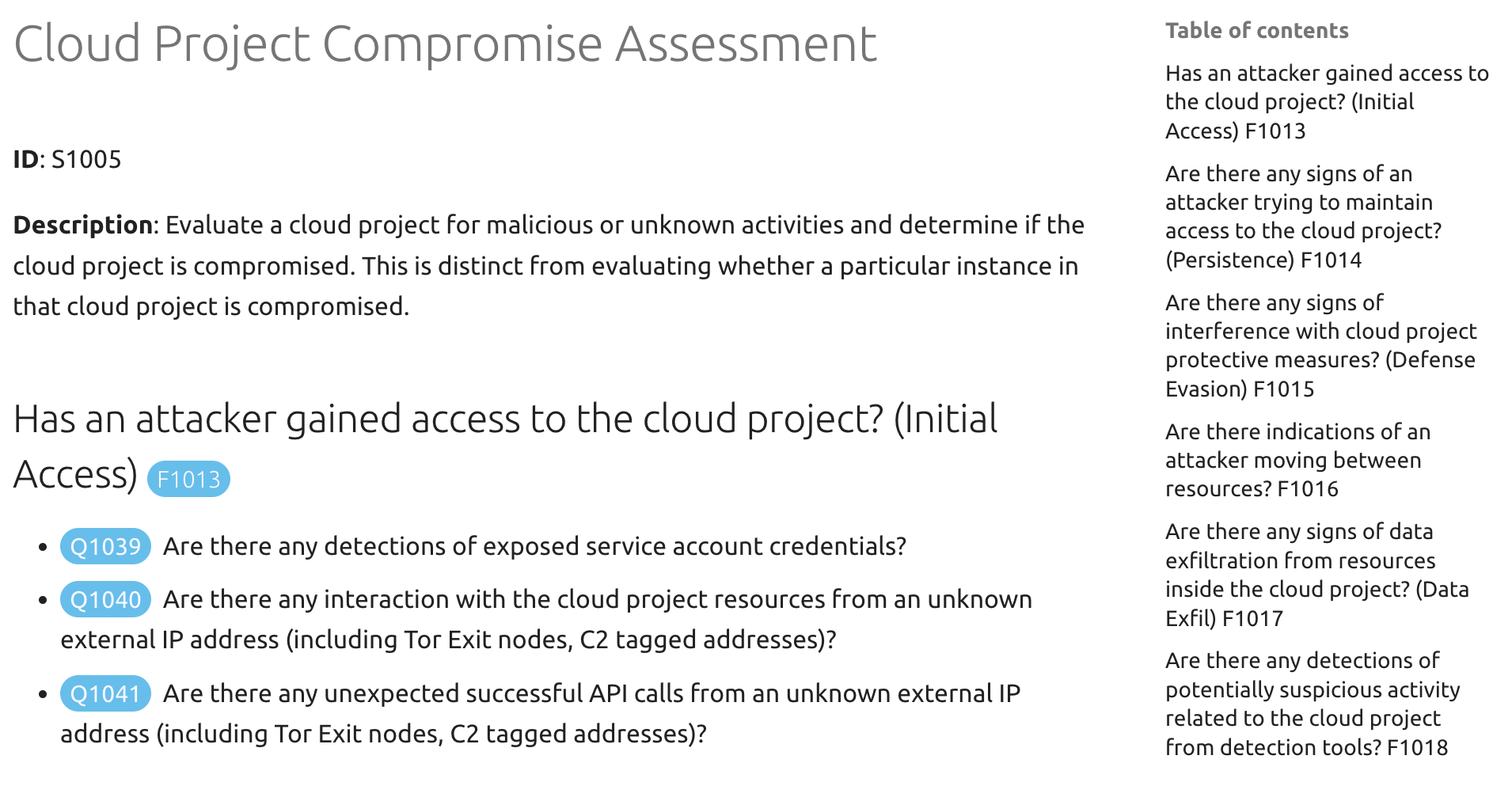

The sad story of CVE-2018-13379 and CVE-2022-40684 (Fortinet FortiOS)

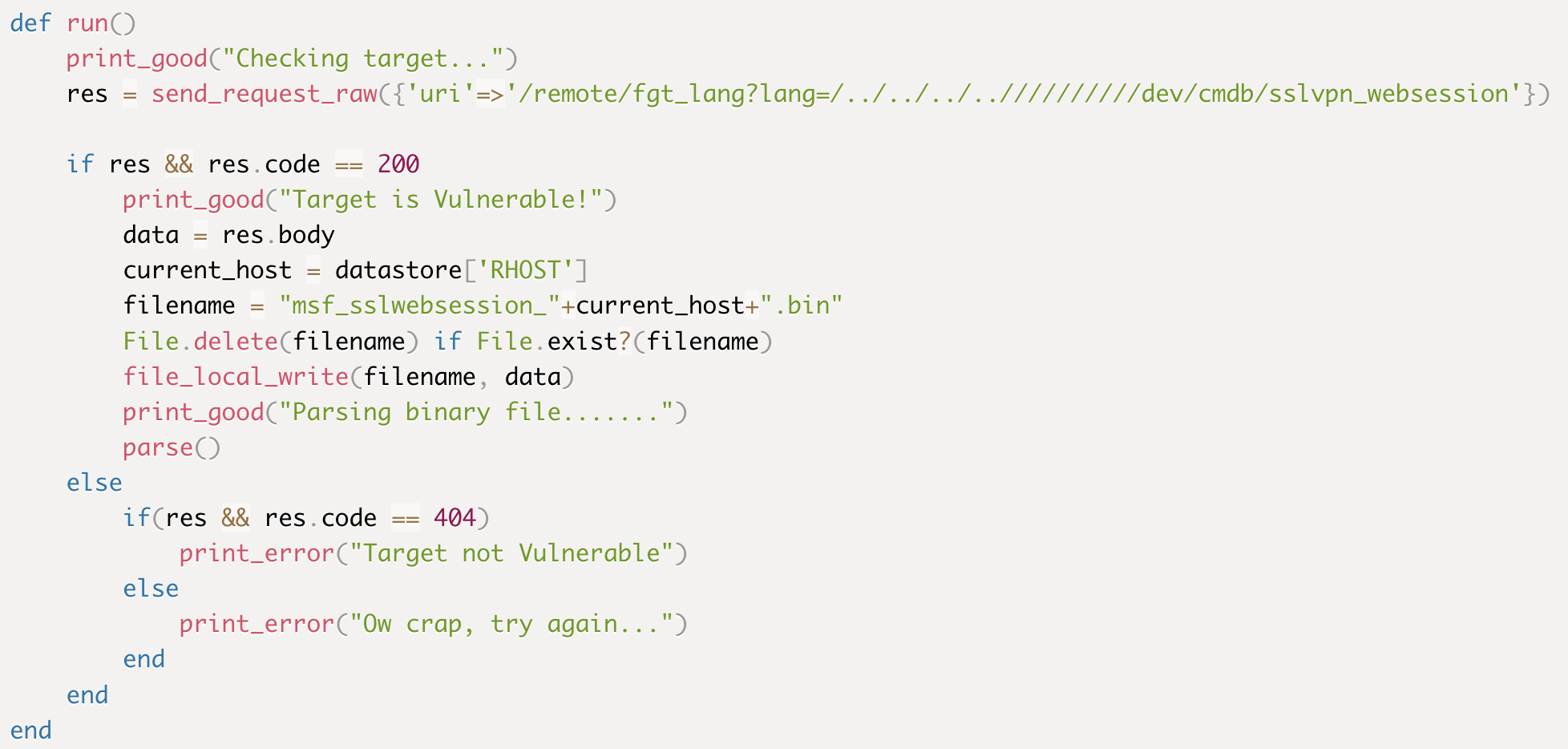

The top exploited vulnerability in 2022 was CVE-2018-13379, a path traversal vulnerability in the Fortinet FortiOS SSL VPN web portal. As the CVE ID suggests, this was assigned in 2018 but not published until June of 2019. Finding instantces to target was as easy as a Google search for intext:"Please Login" inurl:"/remote/login".

In 2019, a pair of exploits for CVE-2018-13379 appeared in Exploit-DB. One of these exploits was a Metasploit module, making exploitation of these systems push-button easy.

Four years after the CVE was assigned and three years after release of an exploit, CVE-2018-13379 was the most exploited vulnerability of the year, known to be leveraged by a variety of successful ransomware groups.

NOTE: This appears to have been used in conjunction with CVE-2022-40684, and it’s unclear why the former topped the last and the latter received an honorable mention.

What will happen in 2023?

It’s impossible to say what 2023’s top exploited vulnerabilities will be. But ongoing and widespread exploitation of products from Fortinet and Cisco, coupled with their place atop the KEV leaderboard as it relates to security controls, are likely to have a significant impact on top exploited vulnerabilities.

Takeaways

This is cursory analysis, but the quality of the underlying data set coupled with what we know about adversary behavior—in particular, that adversaries will always seek out high impact vulnerabilities for exploitation—tells us a lot about the importance of:

- Keeping security controls up-to-date, first and foremost. It’s best to take away the attack surface quickly and proactively.

- Being doubly sure that known exploited vulnerabilities across your attack surface are patched.

- Continuing to put pressure on software vendors to invest in product security, both proactively but also from an incident response and support standpoint.

- Acknowledging that our security controls are high value, high risk, often highly exposed, and treating them as such when it comes to monitoring and threat detection